The History of Comics Grading

As a medium, comic books have had an eventful history. Over the last hundred years or so their public perception has gone from discount entertainment for children, to a niche artform built on long-form storytelling, to now being part of America’s cultural foundation - and a valuable part at that. Market prices for the notable early appearances of icons like Superman, Batman and Spider-Man have been climbing for decades, and the scarce few well-kept copies of these comics are now viewed as investment targets on a par with classic art.

Action Comics #1 - the debut of Superman, the dawn of superheroes in pop culture, and the most valuable comic book on Earth.

What sets these ultra-valuable comic books apart from the rest is the sticker on the top-left - their grade, indicating a nearly century-old comic has somehow been preserved well enough to meet a list of rigorous, exacting quality standards. Who gets to decide which comics make the grade? And how did the grading of comics become such a well-established science to begin with? The answer encompasses a lifetime of work from some of the best-known comic fans in history.

Comics began to find popular distribution in America in the early 1900’s. They were sold on newsstands for a few pennies, with fantastic title illustrations to lure in kids and bored passersby. They were printed on cheap paper with a constantly changing roster of titles and topics, put out by a chaotic group of publishing companies which themselves were prone to rapid collapse or takeover from month to month. This period, which gave us Superman, Batman and the earliest hints of Marvel, would become known as “The Golden Age of Comic Books.”

It was a volatile, trend-chasing business, pumping out disposable pulp entertainment in pursuit of immediate profit. But after the industry’s post-war revival, things began to take on a different cast. Fans who had grown up buying comics were taking a longer view to the medium and its history. Conventions and swap meets allowed passionate collectors to pursue any back issues they were missing and to establish a community of serious comic traders

College professor Jerry G. Bails was a prominent figure in this movement, having begun re-assembling his beloved childhood collection of Justice Society comics by 1953. His constant enquiries to writers and publishers made him a known name, and he used this notoriety to organize many aspects of the comic book fandom. One of the major goals of this organization was to formalize comics trading and reduce instances of fraud or wild speculation as prices for Golden Age issues increased

Bails’s position as a superfan allowed him to publish An Authoritative Index to All Star Comics: Justice Society of America! in 1967 - one of the earliest attempts to establish a consensus market value for historical comics. Bails planned to continue expanding this guide to include data on comics from other series and publishers, but he was soon contacted by another collector, Robert M. Overstreet.

Pioneering collectibles expert and price guide author Robert M. Overstreet.

Overstreet had delved deeply into not only the world of comics, but also other collectibles such as coins and arrowheads, which already benefited from having established and consistent price guides for traders to follow. Even in his youth, Overstreet and his friends had gotten interested in coin collecting through the famous Red Book guides, first published back in 1947. Noticing that the nascent trade in comic books was lacking an acknowledged, definitive guide of that sort, Overstreet began fiercely researching the market value of different issues, gathering data points from dealer listings, collector fanzines, and his own knowledge of recent deals.

When Bails released his Justice Society of America guide to the public, Overstreet immediately recognized the name and realised the authority which Jerry would lend this kind of project. Overstreeet, who did not see himself as having the cachet to write a price guide for comics, wrote to Bails and asked him to author this critical first guide. Bails refused to take full responsibility for the project, but his extensive notes and price recommendations were instrumental in getting the Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide off the ground in 1970 - just in time for comics collecting to blow up.

Overstreet and his staff continue to produce new editions of the famous Guide to this day, keeping the prices up to date with an ever-expanding market.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that the Overstreet Guide marked the beginning of the comics trade we know today. It provided detailed listings of old comics decades before such information could be had online. It standardized prices across the country, and even contributed to their boom by enshrining which comics were the most desirable and valuable.

Crucially, the Overstreet Guide also standardised comics grading. Comic books for sale had long been described with grades like “near mint”, “poor” and “fine”. But traders would grade by their own eye, and each by their own personal standards. For one trader, a comic with its spine protected with tape might be considered well-preserved, where others would deem it totally worthless. Some traders graded covers and pages separately, so a comic could be advertised as having a “Near Mint” grade with the whole front cover ripped off.

The Overstreet Guide published detailed, photoillustrated grading guidelines which served as a baseline expectation of what a “mint comic” really meant. Overstreet also successfully popularized a standard of grading for internal page whiteness, a critical and hard-to-quantify component of a comic’s appeal.

Interior section from Overstreet’s guide to comics grading, which helped to fix standards for what could be considered a Near Mint comic.

Overstreet’s grading system featured 7 grades: Near Mint, Very Fine, Fine, Very Good, Good, Fair and Poor. Like many grading systems, the decision was made not to include an official “Mint” grade - the idea of a truly perfect, pristine comic is essentially mythical and so the line between Near Mint and Mint is dangerously subjective. This system remained in near-universal use for decades. When it was first published the Overstreet Guide listed prices for lower grade comics which were only half or so what was listed for Near Mint. But this shifted over time, with the highest grades of quality inflating in value to dwarf the comparatively worthless grades below Very Good.

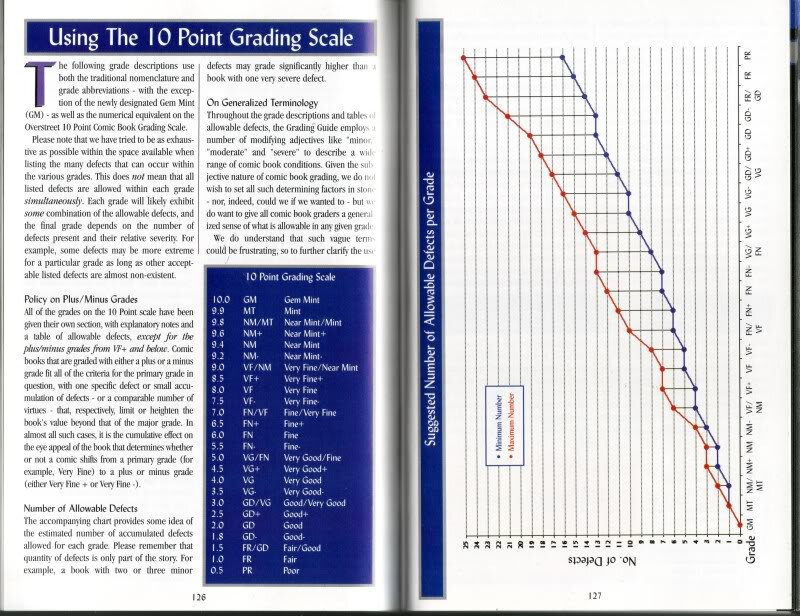

With so much interest concentrated on the highest grades of quality, there was demand for a more nuanced system of grading these comics which could create further subdivisions of value among what was currently all “Near Mint”. The response from the Guide was to publish an amended and expanded grading scale, which used both letter and number grades to emphasize the relatively minor differences between various NM grades compared to the grades down the scale. This Overstreet Numerical Equivalent grade is still in use almost everywhere comics are sold, and has been one of the biggest factors in driving the continuing growth of comics prices.

The final piece of that valuable puzzle wasn’t fully realized until almost the turn of the century. But even by the mid 80’s, Overstreet and his editorial staff on the Guide were talking publicly about the need to establish an independent grading service. Examples of such a thing existed in other fields of collectibles, such as philately (stamps). These experts were not vendors themselves, but acted as consultants to vendors and other collectors who wanted to verify the quality and value of their items. In some cases, the service was provided by an industry-wide professional association.

Current website of the Comics Guaranty Corporation.

But which expert or team of experts would be able to step up and be recognized for this role? Overstreet and his team had their hands full just publishing the annual Guide and its companion pieces - and giving them the role would be an unpopular concentration of power within the community. It took another decade of behind-the-scenes organizing, but in 1999 the Comics Guaranty Corporation was quietly founded with the goal of filling that role as independent grading authority. Comics grading and restoration expert Steve Borock was hired as CGC’s Primary Grader, and he established their policies and practices which have defined the industry since.

CGC has continued to uphold the ONE grading scale, but has refined and standardized the grading process to produce consistent results regardless of which CGC expert handles the job. They also spearheaded the critical switch towards “slabbing” all collector-grade comics within protective plastic cases, ensuring that no further degradation occurs which would invalidate their grading. Slabbing also allowed CGC to attach tamper-proof labels to each case, ensuring the grade was now an unmissable component of the collectible itself.

These changes took a while to gain traction, but a series of unprecedented million-dollar sales in the 00’s seemed to prove that independent grading made a comic more valuable.

Despite the criticism that they alter the fundamental nature of comics as an entertainment and artistic medium, they are now the standard everywhere, with collectors now proudly displaying their shelves of sealed, pristine slabs - for better or worse.

Slabbed comics have become almost a separate market unto themselves; it would be shocking now to see a comic exchanged between collectors without this grading and protective treatment.

The process of standardization begun by Bails and Overstreet and advanced by CGC has become fundamental to what the comics trade is today, to the point that even CGCs competitors tend to piggyback off its established grades. The innovation is now coming from groups which look for a more detailed and nuanced way of analyzing a comics value, such as Quality Evaluation Service. Since the traditional grading by CGC tends to grade a comic by its weakest attributes, QES provides a secondary certification to highlight the strongest attributes of a book, ones which would score a higher grade on their own.

How QES describes its secondary grading services.

The appearance of groups such as QES is evidence of how central grading has become to the world of comics collection; now it is the central pillar of an industry which manufactures attractive, easily identified permanent artifacts for auction houses and investors. Without the additional security and common understanding of value it provides, we would likely still be waiting to see that first million dollar comic book.